Modern Swedish design

Modern Swedish design

Scandinavian Design is a popular label for mid-century Modernism from Denmark, Sweden and Finland. But geographically speaking, the definition isn’t entirely correct – it would make much more sense to talk about Nordic design.

The Nordic countries include all of the above, plus Norway, Iceland and the autonomous territories of Åland, The Faroe Islands and Greenland. We can’t rewrite design history, but as residents of the North we feel that Nordic design would be a more appropriate description.

Anyway. In a series of articles, we will break down the design language of the three major Nordic design nations: Denmark, Finland and Sweden. There are of course many gifted designers hailing from Norway and Iceland as well, but they haven’t achieved the same international recognition – we may however return to them later on.

For this article, we will focus on Swedish post-war design. Spared from the horrors of World War II, neutral Sweden prospered in the late 1940s and 1950s. The economy was strong, and the general quality of living increased rapidly. As people moved into new apartments and houses, demand for new, practical well-priced furniture created a boom in the design industry.

And just as the new homes were based on the functionalist ideals of the 1930s, the design of the time aimed to be democratic and affordable. Modern Swedish design is characterised by functionality, simplicity, ergonomics and honest materials, such as pine, oak and birch. Compared with Danish design, it is less about exotic woods and expert craftmanship and more about rational industrial production.

The goal was to produce affordable furniture “for the many people”, to borrow an expression from furniture giant IKEA. At the same time, the shop and furniture producer Svenskt Tenn, run by Estrid Ericson and Austrian designer Josef Frank, provided high-quality furniture and interiors for the Stockholm elite.

Meanwhile, the prestigious manufacturer and department store NK sought to attract a wider audience by launching their Triva series, which introduced the concept of flatpack furniture. The collective HI-gruppen, consisting of both designers and master craftsmen, pursued a middle path between Swedish rationalism and Danish artisanship, arguing for the value of craftsmanship within industrial production.

While these examples illustrate the stylistic breadth of post-war Swedish design, the functionalist ethos held a firm grip on Swedish modern design well into the postmodern era. Up until the 1990s, Swedish design was hailed for its rational, minimalist aesthetic. Even as a younger generation of designers questioned the status quo with radical and experimental objects, the functionalist ethos survived – and still dominates much of Swedish design.

Below are four designers who, in different ways, have defined, expanded and questioned the DNA of Swedish design.

The icon: Yngve Ekström

Raised in the forests of Småland, Yngve Ekström had a natural connection to the surrounding sawmills and the local furniture industry. In 1945, he founded the furniture brand Swedese with his brother Jerker and business partner Sven-Bertil Sjöqvist. Their ambition was to combine craftsmanship with industrial production. As the company’s chief designer, Ekström designed everything from chairs, sofas and tables to lighting and interiors.

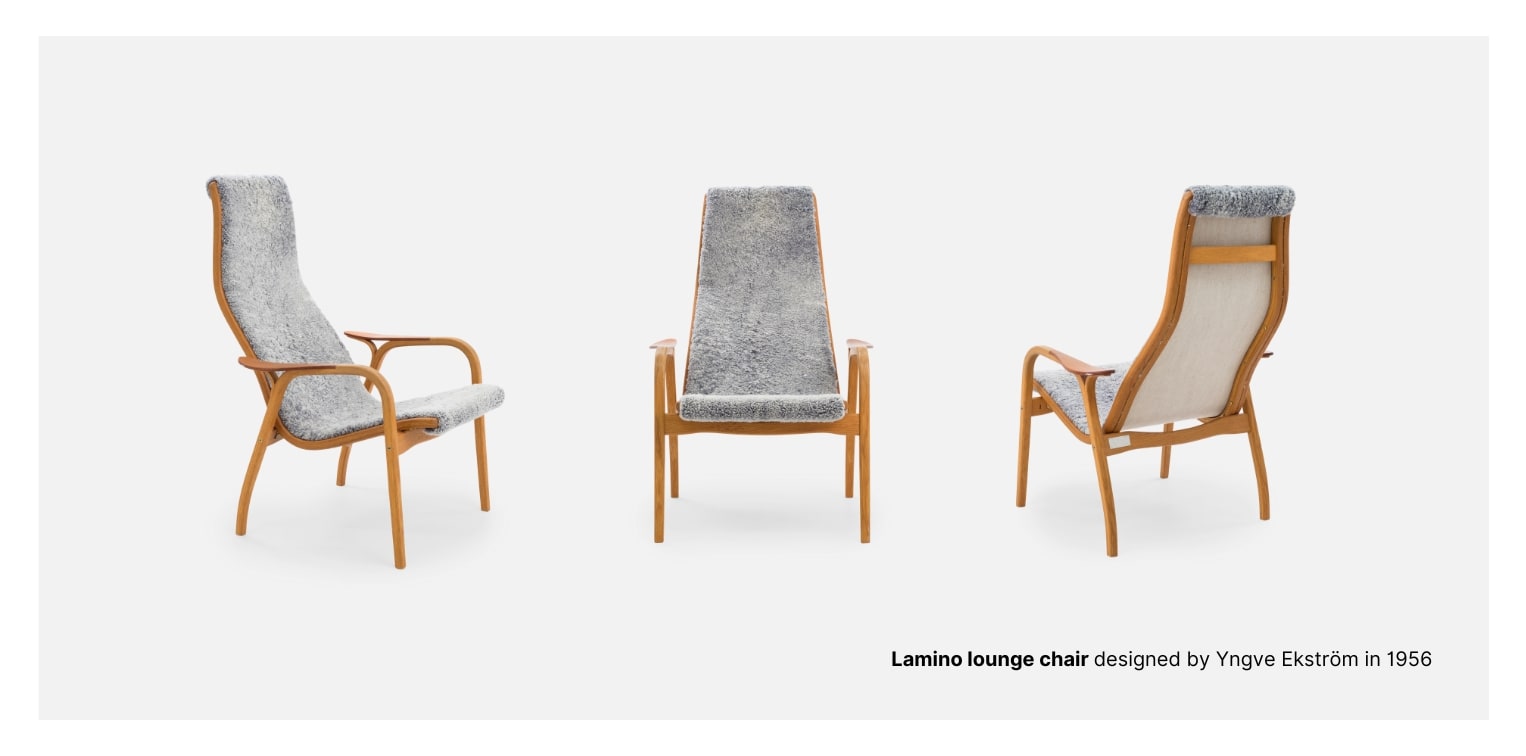

With the easy chair Lamino from 1956, Yngve Ekström produced an enduring classic. Still produced in large numbers, it can be found in offices, public spaces and homes all over Sweden. Made from bent wood and a seat in textiles, leather or sheepskin, the lightweight chair has an elegant and simple S shape, following the body’s contours.

In 1999, Lamino was voted Sweden’s “furniture piece of the century” by readers of interiors magazine Sköna Hem.

The insider’s favourite: Kerstin Hörlin-Holmquist

In the pantheon of Swedish post-war design, Kerstin Hörlin-Holmquist stands out for her humanistic and sculptural reading of functionalism. Creating human-centred chairs that embraced the sitter, she made furniture that was in equal parts comfortable and expressive. After studying at Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design, she began working for the manufacturer NK Verkstäder in Nyköping in the late 1950s. Here, she created her most well-known work, the upholstered sofas and easy chairs that make up the Paradiset series.

The Paradiset sofa in the collections of the Museum of Furniture Studies is a prime example of her aesthetic – with its rounded backrest and splayed wooden legs, it pays tribute to forebears such as Carl Malmsten, while introducing her personal interpretation of Swedish Modernism.

The iconoclast: Yngvar Sandström

Trained as a cabinetmaker at HDK Valand in Gothenburg, the young designer Yngvar Sandström quickly found work at the prestigious furniture maker NK Verkstäder in the early 1950s. Here, he created traditional furniture pieces in teak and other exclusive materials. Some ten years later he moved to Malmö, where he founded the design studio S-Design together with his slightly older colleague Alf Svensson, who had made a name for himself at DUX.

Together, they moved away from traditional materials and production methods, instead favouring contemporary methods and materials – namely plastic. While they still remained loyal to the ergonomic and rational ethos in the work of Mathsson and others, Sandström and Svensson introduced a colourful, youthful aesthetic inspired by 1960s pop culture.

The prime example is the swivel chair Galaxy, designed in the late ’60s and introduced to the market by DUX in 1971. With its moulded-plastic shell it was expensive to manufacture, but its space-age design and comfort made it an immediate international success – inspiring IKEA to commission a similar chair named PLANET from Sandström and Svensson a couple of years later.

The inheritor: Mia Cullin

In her design, Mia Cullin incorporates elements of Swedish Modernism within a contemporary framework. Graduating from Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design in 1998, she opened her own studio soon after and has worked across disciplines with interior design, public environments, lighting, textiles and furniture design.

Her design work is characterised by a structural logic, tactile materials and a sense of poetry. She often works in warm, sustainable materials such as wood, leather and woven webbing. Her Fay Chair (2017), with its light ash frame and woven leather seat, is a perfect example of her ability to achieve a strong visual impact with economical means.